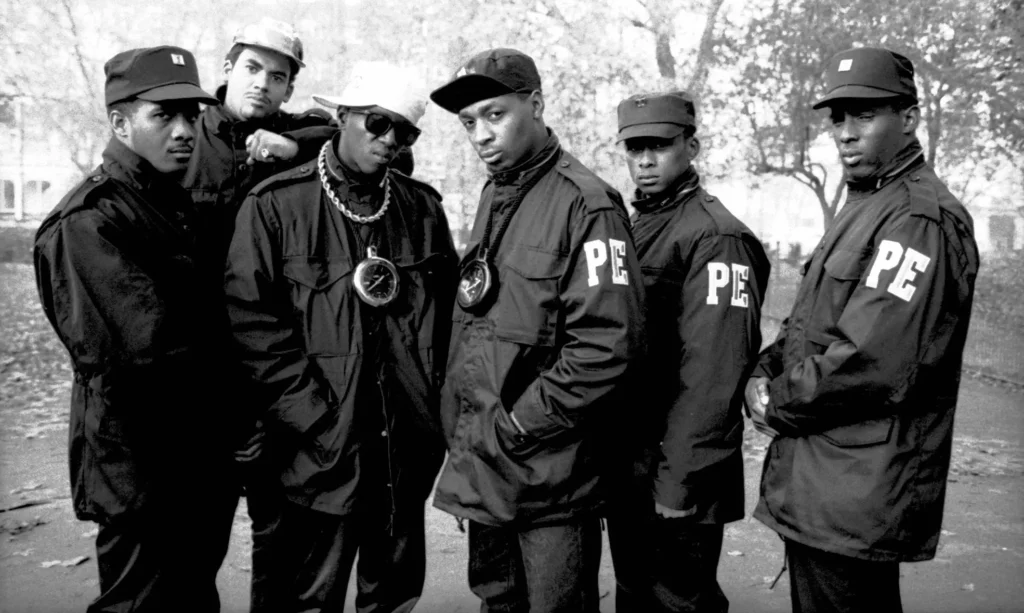

Public Enemy: A New Era of the Black Power Movement

by Nick Hetherington

Hip-Hop was born out of survival, confrontation, and self-determination. The progenitors had a desire to reach people in the community, to have a good time, to speak to a consciousness yearning for personal power, to form a resistance against being treated as second-class citizens, and to gain freedom from oppression. Yet as hip-hop became global in the mid-1980s, the systems of oppression continued to swallow up so many black youths. Stemming from the brutal Reagan years and the roll-back of the civil rights’ movement gains, an evolved apartheid became a stranglehold on urban black neighborhoods. The war on drugs, gang violence, and mass incarceration tore black communities apart, and yet the political activism that had existed in the 1960s was not present in the early 1980s. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated; their voices were too distant to be heard by an untethered, alienated generation who were told [by the society], they only had themselves to blame for their predicament. Through this void emerged a power unit not from the streets of the Bronx, or the projects of Brooklyn or Harlem, but from the middle-class suburbs of Long Island. This unit came to be known as Public Enemy, who saw themselves as part of the continuum of the 1960s Black Arts and Black Power movement. They would not only revolutionize Hip-Hop but would become a potent political force to wake up and re-educate the nation.

The first decade of hip-hop was a celebration of post-gang warfare with rapping and rhyming highlighting good times. Then in 1982, a seismic shift occurred with Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five delivering social protest with “The Message:”

A child is born with no state of mind

Blind to the ways of mankind

God is smilin’ on you but he’s frownin’ too

Because only God knows what you’ll go through

You’ll grow in the ghetto livin’ second-rate

And your eyes will sing a song called deep hate (Grandmaster Flash 4:53).

This moment represents a radical cultural shift and a path forward that illustrates how Hip-Hop could be a vehicle for Black nationalism, and for critiquing American apartheid and internecine destruction. Several years before Public Enemy was discovered, groups formed that took hip hop to extraordinary new territories, and some emerged from middle class suburbia. The formation of Def Jam by Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin brought LL Cool J, The Beastie Boys, and Run DMC into the homes of a new audience. At the same time, members of Public Enemy had already come together, but they had not fully developed the voice that would define them as Hip-Hop’s most dangerous and powerful political revolutionaries.

In the early 1970s, many white ethnic groups–Italians, European Jews, and the Irish– were moving to get away from urban decay and deindustrialization of NYC. The civil rights activists’ dream of integration saw many blacks ready, willing, and able to integrate into New York’s suburbs in places like Hempstead, Amityville, and Roosevelt on Long Island. Black families interested in integration met with opposition, or simply experienced the changing demographics of a town as whites moved farther out on Long Island. As Jeff Chang explains in Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, “white cops treated the black suburbs as an advancing border. Although Blacks made up only 9% of Long Island’s population, they made up over 30% of the arrests in Nassau and Suffolk counties and 43% of suspects shot at by police. These suburban blacks were caught between black poverty and white flight” (9). The core of Public Enemy, Carlton ‘Chuck D’ Ridenhour, Hank Shocklee, Bill Stephney, William ‘Flavor Flav’ Drayton, and Richard ‘Professor Griff’ Griffin, all moved to this suburban area that became known as the Black Belt in the early 1970s.

Chuck D and the rest of The Bomb Squad, aka Spectrum City, aka Public Enemy, were now experiencing segregation and apartheid-style racial steering like their cousins to the west in Harlem and the Bronx. The big difference was that in the suburbs of Long Island, removed from inner-city struggles, the middle-class blacks established successful businesses, and many advanced the culturally rich Black Arts Movement that began in Harlem. Larry Neal discusses the importance and potency of the movement in Drama Review (1968), “implicit in the Black Arts Movement is the idea that Black people, however dispersed, constitute a nation within the belly of white America. This is not a new idea. Garvey said it and the Honorable Elijah Muhammad says it now. And it is on this idea that the concept of Black Power is predicated” (39). Chuck D’s mother Judy Ridenhour formed The Roosevelt Community Theatre and ran it from 1971 – 1985. In 1973, as a young man of 13, Chuck attended several consecutive summer programs at Hofstra to study the Afro-American experience.

By 1977, as Hip-Hop turned five years old, Chuck’s crew would begin to cross paths at Adelphi University in Garden City, Long Island, just as the area was beginning its own nascent Hip-Hop scene. Spectrum City was a DJ mobile unit started by Hank Shocklee, which he migrated from roller rinks to university campuses. In 1979 Chuck was MCing on the microphone, and according to Shocklee, “Chuck was one of the best party MCs of all time” (Chang 17). Bill Stephney was there running the radio show as the program director and invited Chuck and Hank to do the Saturday night rap hour. Public Enemy hadn’t yet been born, but the seeds were being planted. They were creating their own Black Arts Movement on Long Island.

Joining them at the radio show would be a classically trained pianist, William Rico Drayton aka the MC DJ Flava, and Richard Griffin, a martial artist, offered to be Spectrum City’s security. The radio show grew, the parties grew, and next came a recording studio. “Could a Hip-Hop crew break out from Long Island? There was no roadmap” (Chang 24). The next piece of the puzzle gave them their direction, their philosophy, and their cultural and political ascendency, and it tied together, especially for Chuck and his mother’s own Black Arts aspirations.

The inspiration came from Andrei Strobert. He was part of the jazz scene during the 1960s Black Arts Movement and wound up teaching a course called ‘Black Music and Musicians’ at Adelphi during Chuck’s et al time there. Chang points out, “Strobert recognized that Hip-Hop had come out of a traumatic break between generations and he took (Chuck and the crew) back to their roots” (25). Andrei Strobert taught them that, “African music was the source” and “Fats Waller was a rapper. Louis Armstrong was a rapper. Recognize the source. Return to the source” (Chang 26). Chuck D and the other Spectrum City students said the radio executives were starting to call rap a passing fad. Strobert told them, “Don’t Believe the Hype.” Armed with this new motivation, Chuck and the others saw themselves as part of the continuum of the historical movement.

They weren’t the only ones defining the world on their own terms. In 1985 Def Jam Records, spearheaded by the indefatigable Russell Simmons and cultural taste warrior Rick Rubin, was poised to change the record business and Hip-Hop forever. They wanted to take Black culture and promote it everywhere. Rubin famously said, “We are going to win with no compromise.” This meant desegregating MTV and radio. They would take a collaboration between Run DMC and Aerosmith to bring Black rap into the living rooms of white kids unfamiliar with Hip-Hop. They would then bring white rappers in the form of The Beastie Boys into the living room of black kids. By 1986, it was time for the worlds of Def Jam and Spectrum City to collide.

How political could they be, or should they be, was the big question. At first, they went from being called Spectrum City to Public Enemy. This suited them just fine. They considered all the police brutality and modern-day lynching as evidence that black people are the public enemy. They saw themselves as the Black Panthers of rap. They created a furious sound and became known as the Prophets of Fury. They wanted to take on not only Reagan but the Black establishment too. They saw Black radio and Black media outlets as having become obsolete and afraid of being too Black. The 1980s was a new reactionary era that needed media outlets to get on board with the rage and representation. The sense of fitting in and not rocking the boat was anathema to Public Enemy, and they wanted to attack this. Michael Eric Dyson characterizes this in The Culture of Hip-Hop, “rap has also retrieved historic black ideas,

movements, and figures in combating the racial amnesia that threatens to relegate the achievements of the black past to the ash heap of dismemory” (408). Chuck D asked, “How we gonna make our listeners, the Black nation rise?” (Dyson 408). They decided it was on them to illuminate and educate.

Public Enemy’s ground-breaking album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, was a sensation. Dyson explains, “the album’s explicit black nationalist language and cultural sensibilities were joined with a powerful mix of music, beats, screams, noises, and rhythms from the streets. Its message is provocative, even jarring, a précis of the contained chaos and channeled rage that informs the most politically astute rappers” (408). And put another way, right after the album came out in 1988, the Spin Magazine review said, “Public Enemy have not only picked up the torch of black militant politics, they’ve decided to ram it right down the throats of everyone from the government to black radio. If Grandmaster Flash was close to the edge in 1982, Chuck D and Public Enemy have stepped clean over it” (Boyd). Some of the lyrics that were not holding back said, “I got a right to be hostile, my people been persecuted” and “The minute they see me, fear me/ I’m the epitome of the enemy” (Chuck D 0:01). This was going to be an unstoppable juggernaut.

Their music caught the attention of a young filmmaker, Spike Lee. He asked Public Enemy to write him a song for his film Do the Right Thing, a high-pitched, cultural landscape, and pressure cooker, that invited us to observe a day in the life of a Brooklyn neighborhood filled with racism and ending in police brutality. Public Enemy wrote “Fight the Power,” and Spike had the song play from the top of his film, and then all the way through as an aural backdrop punctuating the tension and heat. The song played everywhere that summer, and it lives in multiple visual forms. First made famous in the opening credits of Spike Lee’s film, the song plays in its entirety with a single Latina actress, Rosie Perez, dancing with defiance in front of Brooklyn Brownstones lit in hues of orange and red.

The sound of a helicopter fades in and out, and the audience hears:

While the Black bands sweating,

And the rhythm rhymes rolling

Got to give us what we want,

Gotta give us what we need

Our freedom of speech is

Freedom or death

We got to fight the powers that be (Chuck D 1:00).

They sing “Fight the Power,” and repeat it seven times before the next verse. The actress never stops dancing, but her dancing style changes with crosscuts of her back and forth in different outfits. She has a tight red party dress, an electric blue leotard, boxing shorts and gloves, and a whole lot of non-stop energy and street cred. The effect is alluring, but also menacing. It feels like there is a lot of frustration and pent-up anger. We are being prepared for a potential crisis.

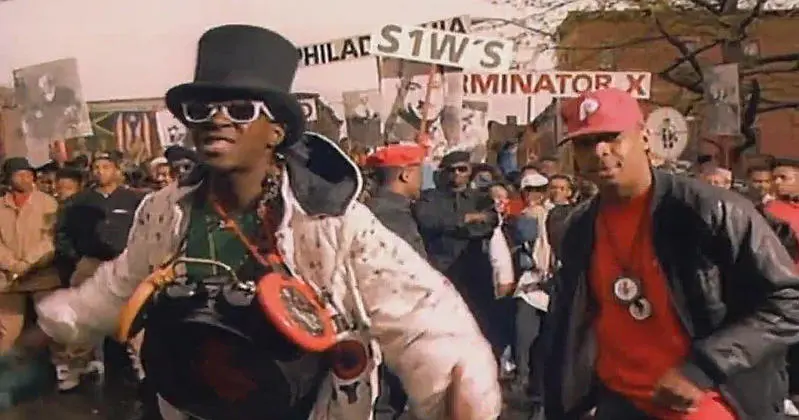

Public Enemy completed an album the following year, Fear of a Black Planet, and included “Fight the Power” as the last track, and with it, they created a music video. If you want to talk about instruments of protest, representation, community, and education all packaged into an art form that thrills, excites and makes you want to dance, there is none other than their video

shot in the streets of Brooklyn with thousands in attendance. Its components are made up of a protest march, concert, dance performance, and political rally, culminating in a determined call for change.

Everything that is Public Enemy is represented.

Every element and aspiration is expressed. You have Chuck D on a megaphone, Flavor Flav doing what only Flav can do; singing, dancing, and performing like a Shakespearean court jester who entertains, but has deep knowledge of current affairs and the psychology of an outcast. Terminator X is scratching and mixing on the turntables. The SW1s are dressed in their Black Panther-style military outfits. The crowd holds up signs of MLK and Malcolm X, reminding everyone that black struggle had once achieved extraordinary political gains from the confrontations of their lost heroes and spiritual warriors, and can do so again.

We have been invited to watch a spectacle of extremes that is asking everyone to wake up and:

Now that you realize the pride’s arrived,

To revolutionize make a change, nothing’s strange

People, people we are the same, no, we’re not the same

Cause we don’t know the game

What we need is awareness, we can’t get careless

You say, what is this?

My beloved, let’s get down to business

Mental self-defensive fitness

Don’t rush the show (Chuck D. 1:45).

They are asking us to prepare our minds, to activate and engage the brain, before agitating and resorting to potential violence. As part of their crew, they also have men dressed like The Fruit of Islam, Louis Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam security force. The video creates and performs a historical narrative. It’s an educational representation of the most powerful leaders being brought back to life. In the same way that you may attend college and a professor introduces important works of literature, philosophy, radical thinkers, political activists, and revolutionaries to open your mind, Public Enemy takes on this role.

It is 1989 at this point, and the Black community around America has suffered enormous losses and political capital. It’s as if the powerful elite, predominately white males, have systematically turned back the clock on progress, and no effective black leader has filled the shoes since the assassinations of the1960s. It’s understandable that if several of the greatest orators and minds of the 20th century are murdered, there is no application you can fill out for that role. First, there must be an individual capable and willing enough to do so, in an environment spilling over with hatred. Dyson captures it another way and states, “this renewed historicism permits young blacks to discern links between the past and their own present circumstances, using the past as a fertile source of social reflection, cultural creation, and political resistance” (409).

The power of Hip-Hop came to fill the void, it became a continuous and evolving art form that birthed a new form of preaching and political activism. Public Enemy became the undisputed heavyweight champions of this evolution, speaking to all generations and reminding people of who has the power and why.

Works Cited

Boyd, Glen. “Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.” Spin Magazine, 1988.

Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Picador, 2006.

Dyson, Michael Eric. “The Culture of Hip Hop.” Reflecting Black: African-American Cultural Criticism, University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. “The Message (Video).” YouTube, 24 Aug., 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=PobrSpMwKk4.

Lee, Spike, director. Universal Pictures, 1989.

Neal, Larry. “The Black Arts Movement.” The Drama Review, vol. 12, no. 4, 1968, pp. 29–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1144377.

Public Enemy. “Fight The Power (Video).” YouTube, uploaded by Channel Zero, 2 Jul. 20, www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmo3HFa2vjg.